Note: this post makes heavy use of MathJax. If you're reading via RSS, you'll want to click through to the web version.

My intuition of regularization is: it's a compromise. You want a model that fits your historical examples, but you also want a model that is "simple." So you set some exchange rate -- the strength of regularization -- and trade off "fit my historical data" against "be a simple model." You meet somewhere in the middle: a model that's simpler than your unregularized fit would produce, but not so simple to the point that it's missing obvious/reliable patterns in the training data.

In the biz, we call it a penalty on complexity, which is different than calling it a ban on complexity. We call it shrinking, which is different than calling it vanishing. These names reflect the intuition: penalize something to get less of it, but not none of it; shrink something to make it smaller, not to make it disappear. With regularization, we'll reach some compromise point, and get a model that (a) is less well-fit to the training data than in the unregularized state, but also (b) not maximally, uselessly "simple."

This blog post is about how the world's most famous regression scheme, the Lasso (Tibshirani 1996), rejects compromise. For certain, sufficiently-high penalty rates, it will quite happily only give you a maximally-simple model: one that zeros out consideration of any predictive features you handed it. No compromise, just an all-zeros empty model; "I found no pattern in the data." And people love this about the Lasso! My dissertation was built on this property, where Lasso regularization can zero out model weights.

But it's also weird to me that it's possible, given what I thought we were doing by regularizing a model fit. It's not a compromise anymore.

Why's Lasso do that?

What's Lasso? (A convex optimization.)

It's typical for statisticians to formalize "fit the data, but with a simple model" by posing an optimization task built on five raw ingredients:

- Defining "the data" as a collection of \(N\) examples, represented as vector-scalar pairs, \(\left\{\vec{\mathbb{x}}_j, y_j\right\}_{j = 1}^N\) Each \(\vec{\mathbb{x}}_j\) is in \(\mathbb{R}^p\) (call each of these an example's feature vector) and each \(y_j\) is an example's scalar label.

- Defining the model as a vector of \(p\) parameters, \(\vec{\mathbb{w}} \in \mathbb{R}^p\). Call each individual parameter (i.e., each vector element \(w_i,~i = 1, \ldots, p\)), a model weight.

- Defining a function, \(f\left(~\cdot~; \left\{\vec{\mathbb{x}}_j, y_j\right\}_{j = 1}^N\right): \mathbb{R}^p \to \mathbb{R}\), that expresses goodness-of-fit. By construction of \(f\), a model parameter vector that minimizes \(f\) corresponds to a model that's "fitting the data" to the best possible extent. Call \(f\) the loss function.

- Defining a function, \(r: \mathbb{R}^p \to \mathbb{R}\), that expresses model simplicity. A model parameter vector that minimizes this function corresponds to a maximally simple model. Call \(r\) the regularizer.

- Defining a scalar hyperparameter, \(\lambda \geq 0\), that defines the strength of regularization. The bigger \(\lambda\), the more we favor \(r\) over \(f\).

Mixing these together, our optimization task is:

Lasso's loss function

Our loss function is defined as:

That's:

- the sum, over the features-and-label pairs for all \(N\) examples,

- of the square

- of the difference

- between the actual label \(y_j\)

- and the dot product of \(\vec{\mathbb{w}}\) and \(\vec{\mathbb{x}}_j\)

The model weights "fit the data" by producing a weighted sum of the example's features that is a reliably close match to the example's scalar label. The loss function is a sum of squares, so it's always non-negative. The closer it is to zero, the better the average label match we are getting from our model weights. Minimize the loss function to best fit the data, just how we wanted.

Lasso's regularizer

Our regularizer is:

the \(L_1\) norm of our model weight vector. Models with weights that are reliably close to zero count as "simpler" than ones with larger-magnitude weights. Just like \(f\), \(r\) is always non-negative. We can minimize it by choosing a weight vector of all zeroes. The model that always picks "zero" as its guess for \(y\), totally ignoring the example's features, is this regularizer's simplest possible model.

Lasso's convexity

Altogether, the optimization task is:

Take on faith that this mixture of \(f\), \(r\), and \(\lambda\) is convex. \(f\) and \(r\) are both convex, and \(\lambda\) is non-negative, which lets us argue

- the scaling-up of a convex function by a non-negatve value is itself convex, so \(\lambda r(\vec{\mathbb{w}})\) is also convex,

- the sum of two convex functions is itself convex, so the overall mixture \((f + \lambda r)\) we're minimizing is convex.

Convex functions come with a lot of nice properties I will leverage later on, so I want to emphasize the convexity of our optimization task now.

Dropping down to univariate Lasso

At this point, we'll take a special case: when \(p\) is 1. This univariate regression means both (a) our weight and (b) each example's feature "vector", are just plain ol' scalars. Our optimization task, with \(w \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(x_j \in \mathbb{R}\):

I promise we're reinflate this to the multivariate case before we're done. Lasso's convexity will help a lot with that.

But now that we're down here, we celebrate that low dimensionality means we can make charts. Charts!

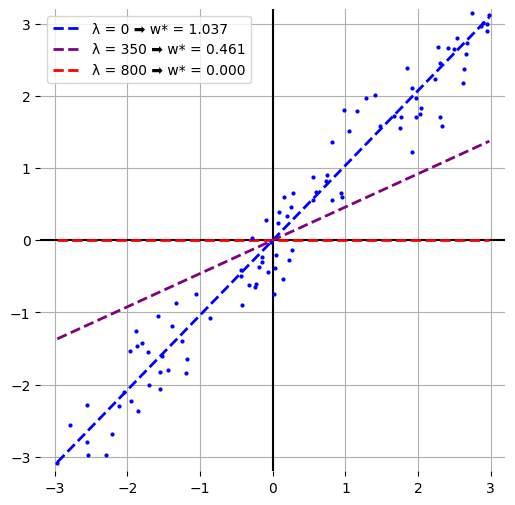

Here's a dataset with a clear relationship between \(x\) and \(y\). The data are plotted as blue dots. I fit three Lasso models to this dataset, with \(\lambda\) taking on values of 0, 350, or 800. I overlay the dashed trendlines each model produces for the range of \(x\)'s, and we see those three trendlines decay from a slope of 1 to a totally null (maximally simple!) slope of zero:

- The model with least regularization, \(\lambda = 0\) in blue, has a trendline that best fits the data.

- The purple line, \(\lambda = 350\), is not a great fit to the data, but at least is directionally correct when it identifies a positive correlation between the example feature \(x\) and the example label \(y\).

- The red line, \(\lambda = 800\), totally ignores \(x\) and always predicts that \(y\) is zero. This is what you get when \(w^*\) is maximizing \(r\) with no regard for \(f\).

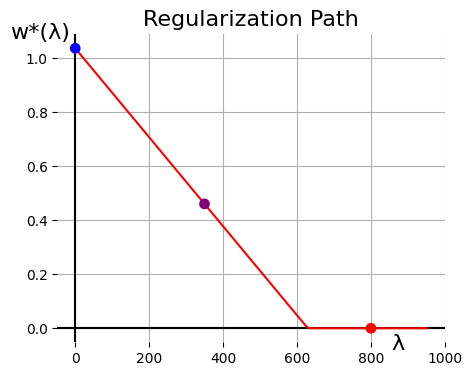

If we repeatedly produce a model weight \(w^*(\lambda)\) for many more values of \(\lambda\), we can see this decay evolve in more detail (with our three models above appearing as special large dots):

As regularization strength increases, the resulting model weight drops linearly, until it hits absolute zero. Early on, you see compromise between \(f\) and \(r\): \(f\) wants a slope of 1, and \(r\) wants a slope of 0, and as we strengthen \(r\)'s negotiating leverage, we get models that look more and more like what \(r\) wants. Not entirely what \(r\) wants: we still pick up on the positive correlation that lives in the data. We don't discard \(f\)'s fit-the-data contributions entirely.

But past \(\lambda \approx 630\) or so (spoiler: I give you the exact formula for this breakpoint a few sections from now), the optimization is ignoring the \(f\) completely. That fit-the-data component is still there as part of the objective to be minimized, and yet there's no compromise: the model weight returns what \(r\) wants, and only what \(r\) wants. It's like \(f\) isn't even there, except it is. We never zero'ed \(f\), we just amp'ed up \(r\).

What's Lasso doing? Why's Lasso do that?

What's Lasso doing? (Parabolas.)

Lasso is making our optimizer follow the instructions of a pair of parabolas. When we strengthen regularization past a certain point, we're not able to make either parabola happy, and bounce back and forth between them until we're stuck at \(w^* = 0\).

Zero regularization

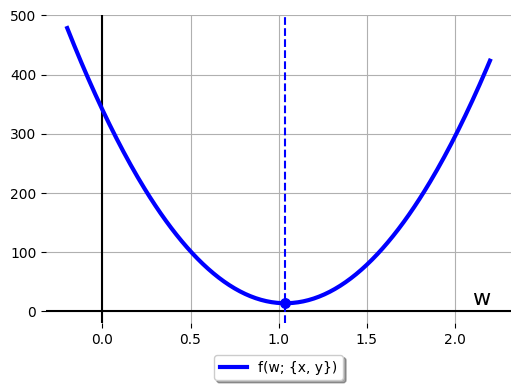

When there's no regularization at all, at \(\lambda = 0\), our optimizer's objective is just to minimize the loss function \(f\), the sum of squared errors:

If we rearrange \(f\)'s terms a bit, we'll see it's a parabola as a function of \(w\):

Define some helpful aliases for those terms,

where \(S\)'s stand for sums of squares our features or labels and \(D\) stands for a dot product of feature and label. That makes the parabolaness of the unregularized loss function really stand out:

The vertex of a parabola like this lies at the famous "\(-b/2a\)" point, which means \(f\) is minimized at:

(Or, expanding those terms for the fun of it:)

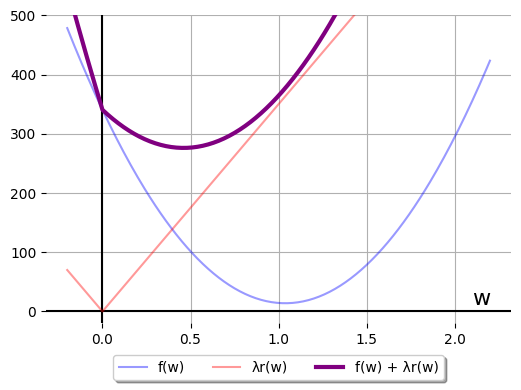

Let's plot \(f\left(w; \left\{x_j, y_j\right\}\right)\) for the blue-dots dataset we used above:

We use an optimization routine that implements some kind of descent method to start with any arbitrary guess at the \(w\) that minimizes \(f\), then refines it until it finds the actual minimum. Imagine this optimization routine as a little guy, wandering back and forth along the range of \(w\) to minimize \(f\). Lasso's loss function parabola gives our little optimizer guy unambiguous instructions:

Wherever you are right now, move towards \((D_{xy}/S_x)\). As long as each step puts you lower than you were before, you will find the minimum.

If the little optimizer guy loops that enough, he'll land at \(w^*(0)\).

Some regularization

When we increase \(\lambda\) to some positive value, we're adding \(\lambda r(w)\) to the function we want our little optimizer guy to minimize. That scaled regularizer is a function that looks like:

It's a piecewise linear function, with a negative slope on the left-hand side (LHS) and positive slope on the right-hand side (RHS). When we add \(f\) to this, we wind up with a piecewise quadratic function:

These two parabolas, LHS and RHS, have "\(-b/2a\)" vertices aligned at:

This function provides our little-guy optimizer a more complicated set of instructions:

- While you are on the LHS: take descent steps towards \((2D_{xy} + \lambda)/(2S_x)\). If your latest step took you out of the LHS, this rule no longer applies.

- While you are on the RHS: take descent steps towards \((2D_{xy} - \lambda)/(2S_x)\). If your latest step took you out of the RHS, this rule no longer applies.

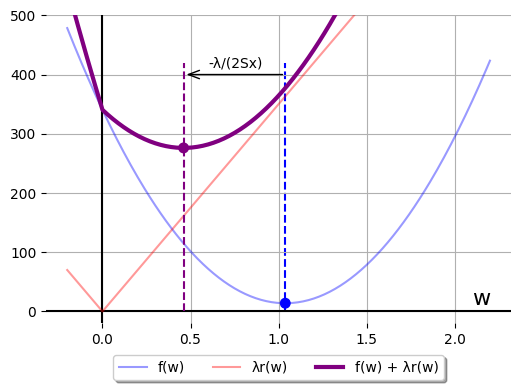

When regularization is non-zero, but light, the optimizer can resolve this without too much extra effort. We saw a case like that above, when we set \(\lambda = 350\) for our blue-dots dataset. Here's what the mixed objective looks like, where the purple series is the sum of the blue and the red:

Imagine the little guy starts at \(w = -1\). His thought process is:

- "I am starting on the LHS. The LHS instructions say I should head to \(w = (2D_{xy} + \lambda)/(2S_x)\)."

- [later:] "I've taken a lot of steps, and not reached \((2D_{xy} + \lambda)/(2S_x)\), and I have in fact crossed the \(w = 0\) border. I'm on the RHS now. My instructions from Step 1 no longer apply."

- "My new instructions, now that I'm on the RHS, say to head to \(w = (2D_{xy} - \lambda)/(2S_x)\) instead."

- [later:] "OK, made it. I am at the vertex of the RHS parabola, which is on the RHS (i.e., I never re-crossed the \(w = 0\) border)."

- "My instructions are still the same as they were in Step 3, and I've finished following them. Job's done."

The difference between \(w^*(0)\) to \(w^*(350)\) is shrinkage: the vertex of the RHS parabola is \(-\frac{\lambda}{2S_x}\) units smaller than the zero-regularization vertex:

Neither \(f\) nor \(r\) are minimized at that points where they intersect the purple vertex axis of symmetry. Both could be much smaller, if they didn't have to accommodate the other. That's a good compromise: one that leaves everyone angry.

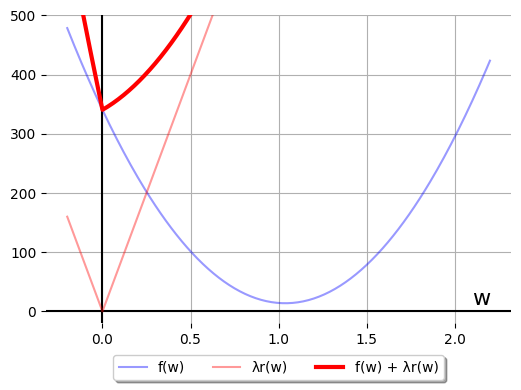

Lots of regularization

When we ramp up our value of \(\lambda\) from 350 to 800 on our blue-dots example, nothing about the rules change for our little-guy optimizer. What does change is the layout of the two parabolae: now, neither parabola's vertex lies on the side its rule governs:

The thought process for our little guy is:

- "When I'm on the LHS, it wants me to go to \(\left(2D_{xy} + \lambda\right)/(2S_x)\), which is on the RHS."

- "But then when I get to the RHS, it wants me to go look for a minimum at \(\left(2D_{xy} - \lambda\right)/(2S_x)\), which is back on the LHS. I just came from there!!"

For some optimizers, this bouncing back and forth can take awhile to resolve. But when it does resolve, it can only end at \(w^*(800) = 0\), the maximally simple model weight.

When does this happen? It happens when both the LHS and RHS parabolae have vertices centered on the opposite side. This can happen no matter the sign of \(D_{xy}\), so long as \(\lambda\) is big enough.

- If \(D_{xy} > 0\), the unregularized vertex is on the RHS. Ramping \(\lambda\)

such that the RHS vertex \(\left(2D_{xy} - \lambda\right)/(2S_x)\) is

pushed to the LHS means:

$$2D_{xy} - \lambda < 0 \Rightarrow \lambda > 2D_{xy}$$

- If \(D_{xy} < 0\), the unregularized vertex is on the LHS. Ramping \(\lambda\)

such that \(\left(2D_{xy} + \lambda\right)/(2S_x)\) falls on the RHS means:

$$2D_{xy} + \lambda > 0 \Rightarrow \lambda > -2D_{xy}$$

We can combine these two criteria -- "if \(D_{xy}\) is positive, double it" and "if \(D_{xy}\) is negative, negate it, then double it" -- into one rule that determines when our minimum will be at \(w = 0\):

This is the magic threshold for Lasso. Past this level of regularization, we can only get the empty model out of the optimization.

Checking my work: in the blue-dot case, \(D_{xy} = 314.7\), and the "Regularization Path" figure shows that \(w^*(\lambda)\) hits zero right where we expect, around \(2 \times 314.7 = 629.4 \approx 630\).

It's good to know Lasso has this magic threshold: often we will tune the regularization parameter so that we can find a model that works well on held-out test data. With this magic threshold, we can put an upper bound on our search space: past \(2|D_{xy}|\), we will always get the same zero-model result. We don't need to keep searching past that threshold value. That's useful!

Why's Lasso do that? (Discontinuous slope.)

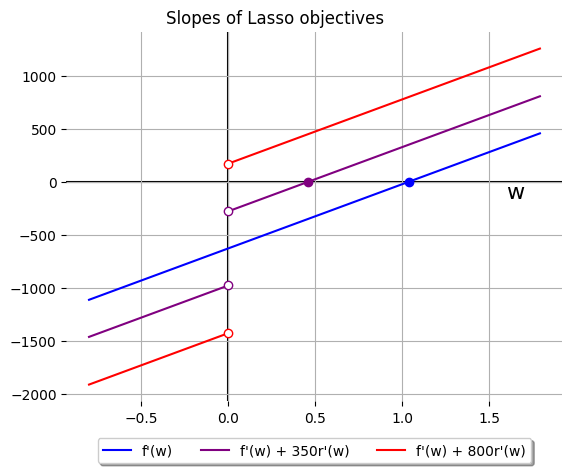

The slope of our Lasso objective looks like:

Note that part and parcel of Lasso's convexity means this slope is never decreasing. In this univariate case, that's the definition of a convex function, which we know Lasso to be.

The derivative for our regularizer hits a snag at \(w = 0\); the slope tangent to \(|w|\) depends on whether you mean "sloping in from the LHS" or "sloping in from the RHS":

We can plot this for the zero-, some-, and lots-of-regularization models fit to the blue-dot data, where we see a steadily larger discontinutiy at \(w = 0\):

(Side note: in an alternate case where \(D_{xy}\) is negative, this plot of slopes will look very similar. Lasso is still convex, so these slope curves must still all be non-decreasing. The difference would be that the blue and purple vertical-axis-intercepts would be positive instead of negative.)

For zero- and some-regularization, the blue and purple lines, we see intersection with the horizontal axis at the same points we see the vertices of their respective parabolae above: \(w\) values where our Lasso objective has zero slope.

But with lots-of-regularization, there's no similar intersection. The discontinuity introduced by \(\lambda r(w)\) is large enough that, at \(w = 0\), the slope jumps straight from "very negative" to "slightly positive." This pseudo-intersection with the horizontal axis determines where our little-guy optimizer halts, just like the genuine points of zero slope in the blue and purple models.

Looking at the slope discontinuity explains Lasso's magic threshold \(\lambda > 2|D_{xy}|\) in a way that generalizes to other loss functions for \(f\). The regularizer is acting like a kind of crowbar, chiseled into the unregularized objective at the point \((w, f'(w))\), and prying the LHS and RHS apart from each other by an additive factor of \(\lambda\).

Our blue slope line has a non-zero value at \(w = 0\). For \(\lambda|w|\) to introduce a sign change in the slope, it either needs to push a positive \(f'(0)\) below the horizontal axis, or (as in the blue-dots example here) push a negative \(f'(0)\) above the horizontal axis. As in, we get the maximally-simple model whenever we set:

For original-recipe Lasso, where our loss \(f\) is the ordinary least squares function, \(f'(0) = 2D_{xy}\). Plug that in above and recover the magic threshold. Without any regularization (for \(D_{xy} > 0\) here, but the logic holds in the mirror case, too), \(f(w)\) decreases as you move from \(w = 0\) into the RHS. Even with some regularization, \(f(w) + \lambda r(w)\) decreases as you move into the RHS -- it has a negative slope at \(w = 0^+\).

In sum,

- The function we're optimizing is convex, so its slope is non-decreasing. If out little guy is ever at a point where the slope is negative, it must move right to hope to reach a minimum where the slope is zero. And if it's ever at a point of positive slope, it must move left.

- With the discontinuity of Lasso's regularizer, we see two different slopes at \(w = 0\), depending if we approach 0 from the LHS or the RHS.

- When \(\lambda\) is big enough, relative to the slope \(f'(0)\), these two slopes will have opposite signs. The sign of \(\left[f'(-\epsilon) + \lambda r(-\epsilon)\right]\) will be negative, and the sign of \(\left[f'(-\epsilon) + \lambda r(-\epsilon)\right]\) will be positive, for any \(\epsilon > 0\).

- And so we get stuck right at \(w = 0\). Try to move a bit left off zero, to \(w = 0^-\), and you will sense a negative slope, and get told to move back right. Try to move a bit right, to \(w = 0^+\), and get told to move back left.

- The little guy optimizer gets driven to \(w = 0\) itself, and can't go anywhere else.

That's why Lasso does that.

Returning to multiple features

This same phenomenon applies even when we reinflate from \(p = 1\) univariate feature, back to the \(p > 1\) multivariate case. Lasso does this in high dimensions, too.

Bringing back our original \(N\) vector-scalar pairs, \(\left\{\vec{\mathbb{x}}_j, y_j\right\}_{j = 1}^N\), I'm going to define some new helper aliases. First, imagine stacking all the feature vectors, transposed horizontally, into a matrix \(\mathbf{X} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times p}\):

Now imagine pulling out the \(i\)th column from that matrix: it encodes the \(i\)th predictive feature for each datum \(j = 1, \ldots, N\). Call each of these column vectors \(\vec{\mathbb{x}}^{(i)} \in \mathbb{R}^N\), \(i = 1, \ldots, p\):

And let's also pull the labels \(y_j\) into their own column vector:

Imagine, for our multivariate dataset, we have currently set our little-guy optimizer at the fully sparse, all-zeros weight vector, \(\vec{\mathbb{w}} = \vec{\mathbb{0}}\). What would it take to convince the little guy to move any single model weight off of zero?

The little guy can consider each feature, \(\vec{\mathbb{x}}^{(i)}\), one at a time, as if each were its own individual univariate Lasso case. The current weight vector ignores every feature, so the question of "should we put any weight on feature \(i\)?" depends only on the univariate dataset \(\left\{\vec{\mathbb{x}}^{(i)}_j, y_j\right\}_{j=1}^N\); the other features are currently zeroed out and of no concern.

For feature \(i\), the magic threshold is the analogue of \(2|D_{xy}|\), taking a dot product between the \(i\)th feature column vector and the label column vector:

The little guy will not move off \(\vec{\mathbb{w}} = \vec{\mathbb{0}}\) if \(\lambda\) is big enough to cross the magic threshold for all \(p\) features. Which means have a meta-magic threshold in the multivariate case that zeros out all \(p\) model weights, just by ramping \(\lambda\) to a big enough value:

(Note that the \(\max_i\) operation is the same as, for our definition of matrix \(\mathbf{X}\) above: "calculate the vector \(\mathbf{X}^T\vec{\mathbb{y}}\), then find the largest-magnitude element.")

This is also good to know! If we're using crossvalidation to hunt for the perfect \(\lambda\) parameter, it continues to be nice to have an upper bound on the search space. It's good to understand why a statistical technique works.